...continued from Part 1: Language and the Chart

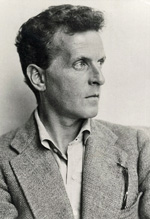

Part Two: Wittgenstein and Language Games

Ludwig Wittgenstein introduced his concept of 'language games' to highlight the fact that words have a multiplicity of usages. They can make sense in all sorts of ways, and in each of these ways they follow a rule, but none of these rules apply across the whole of a language, for each is unique. Nor is there any hope that the scientific approach of seeking underlying principles or causes can be used for such concepts as 'principles' and 'causes' are themselves examples of different ways of using language. What can be thought of as a cause in one circumstance cannot be considered causal in another, as the rules are different in each case.

When Wittgenstein speaks of our 'following a rule' he is referring to a consistent use of language in a particular case. If someone declares that their heart is full of love, they are using the concept of the heart as a container in a poetic way. This is quite different from the manner in which a doctor might speak of the heart as being full of diseased material, and if anyone really believed that the heart was literally full of a substance called 'love', then they will have failed to grasp the complexity of language. Young children typically have that problem when they are learning to find their way with words. One client told me that, as a little girl, her uncle had died on holiday, and she had heard her parents say that his body was being brought home. She was alarmed, as she wondered what would be done with his head and arms. Later she would learn that 'body' can also mean a group of people, that the body can be politic, that there can be a body of water or a body of opinion. In each case a different rule of usage is being employed, which we can see at once, although there can be no universal rule that will explain which is the correct usage. Wittgenstein named these different ways of using words 'language games'.

He used the word game because all games have rules of some kind, and it is these rules that make the game possible. Chess is a game, and so is football. Both involve strategy and movement, both have players with different functions, both have legal and illegal moves, and both are carried out to win. However, both games are also totally different, and do not have interchangeable rules. So, it is with language. Making a move in chess is completely unlike making a move in football, so if we think that a heart full of love is the physical description of an object, we have completely missed the point, and are putting on football boots to play chess.

The various ways of using the same word, and the fact that it will have a different meaning in each context, is the core idea of the 'language game'. In short, the meaning of a word always lies in how it is actually used. To tell someone to 'keep their shirt on' is not an instruction to remained clothed, but to stay calm. Asking for a screwdriver in a hardware shop will not produce the same item as asking for one in a cocktail lounge. This point cannot be over-emphasised: the meaning of a word lies in how it is used, and what takes place in life as a consequence of its utterance.

This may sound as if language games are quite arbitrary and that so long as we are consistent in our usage one thing is as good as another. However, such is not the case. For a language game to 'work', to be seen by people to be relevant to their lives, it must relate to the nature of the world. It's no good inventing a language game of colours if there were no colours to perceive in the first place. It is the nature of the world that ultimately dictates whether a language game is valid, not some personal feeling or theory about it. It is the universal quality that Wittgenstein recognised - and the key elements of astrology are universal – that lead also to refer to language games as 'forms of life.' Most language games are inherently connected to specific 'forms of life.' Others, like astrology span a variety of usages simultaneously, and thus can be applied to a wide range of situations, from delineating personality traits to forecasting weather patterns and stock market movements, from predicting world events to planning the planting of vegetables, and from choosing opportune moments to commence business ventures to identifying genetically inherited illnesses. The same signs and planets will be involved in all cases, but their interpretations will vary according to the circumstances.

There can be little doubt that astrology is a complex language game. It has its own rules, and ways of talking about life and the world that are relatively consistent and coherent. But the point that is invariably raised against it is this: does its language refer to anything real? That is, do astrological statements carry the same validity as claims such as 'humans are mortal,' 'ice is cold,' 'the earth goes round the sun'? Or is it merely a poetic way of talking about our experience of such phenomena?

The Astrological Language

Astrology offers us a way of describing and talking about the world, just as science does, and, like scientists, astrologers can get carried away by language into reification, where a description is magically turned into a casual principle, and a way of talking about something becomes an operating system to explain what has been observed. If we stay with description, we can recognise that astrology uses the word Mars to denote anger, Saturn to signify guilt, Aquarius to stand for innovation, and so on. Again, at this level, there are no problems for either the scientist or the philosopher. There is no logical reason why the word Mars cannot be used to denote anger, any more than there is a logical reason why we should quibble over calling someone 'sad' or describing them as 'unhappy'.

We know that some people are more assertive than others. The astrologer would say that such people 'have a strong Mars.' At this level the two statements are identical. To say of someone 'he is assertive' or 'she has a strong Mars' means the same thing, and our choice of description merely a matter of convention. Astrologers often make the mistake of pointing to Mars in a such a chart and saying that its placement 'explains' the personality of the native. It does not. It offers a description. To speak of explanations here is to fall into the language game of science, and take on some of science's inherent confusions.

The astrologer's way of talking may be better in some circumstances, and worse in others, as is true for all languages. For some the problem might start with the astrologer's claim that their language uses the names of the planets and signs, not for reasons of poetic whimsy, but because the positions of the planets and their movements through the zodiac dictate how the language is to be used. But all language-use and understanding depends on the manner in which signifiers shift their representation against the background of different circumstances. Similarly, all language is above and beyond us, and many philosophers and psychoanalysts take it for granted that to some large extent we are its creation.

Such views give us the image of language as alive and powerful with a drift and movement of its own. They portray humanity as created and structured by the nature of language itself, which has obvious implications for the astrologer. Language is far from being 'natural' and 'within us.' It is akin to an alien life form into which we are born, and into which we must fit ourselves. We are limited by the possibilities of language to the extent that even the physical body is named and determined by the conjectured power of words. Wittgenstein, too, draws our attention to language as the final limit of our world. It is only when astrology insists that the positions of the planets are the moving signifiers of life that it goes beyond current philosophical thinking. Here we ought to consider if the views of astrology must fall by the wayside because a key claim appears to find no support in language theory, or whether astrology itself can extend the boundaries of our concepts of language, and thus contribute to (and not fall victim to) current limitations of thought. Though we could also note that a major feminist philosopher of language, Luce Irigary, wrote that women had 'an irreducible relationship to the universe'[11], a claim that might also be extended to men.

Losing our Causes

As the positions of the planets are central to astrology's language, it follows that their changing positions can signify possibilities for current or future events. There is also no doubt that this second claim is somewhat at odds with scientific and philosophical thought, even if science can make its own predictions based on interpreting mathematical symbols, some of which are more successful than others. Here we should start with one of the most common objections: no causal mechanism exists which explains how the position of a planet can correlate with a specific event or character trait. First, we should note that when scientists search for a cause they tend to ignore the fact that causality is not a law which nature obeys, but the form of words, the mindset, in which science states its propositions about nature, an attitude which tends to cast its shadow on the question. However, in the case of astrology the question is fatally flawed, giving a graphic example of what Wittgenstein meant by being 'bewitched by language', in this case the language of causality.

For the astrologer the specific position of Mars in the sky might signify a particular possibility on Earth or a characteristic of someone born at that moment. If that is so, then what part could causality possibly play? If the position of Mars means such-and-such, and this indeed does occur, to suggest that such a description causes the phenomenon it describes demonstrates only confused thinking. The meaning of something cannot act causally to bring about the phenomenon which is implicit in the description. This is so for all languages: they either describe a state of affairs correctly, or they do not, and this is either meaningful or not meaningful for an individual. Meaning does not have a location, it does not arise from an object, any more than the meaning of a news story lies in the nature of newsprint and ink, or the meaning of a television report lies in flickering electrons. While some astrological researchers are still tempted by the idea of physical causality[12] [13] language is not a causal agent, but a mode of description. A particular description may alter or expand one's perspective of a person or an event but it does not create it - obviously so, as description is invariably post facto. This is to some extent the same when either the scientist or the astrologers makes predictions. In both cases a possible state of affairs is described using their respective languages in a meaningful way.

Finding meaning and seeing connections is a human act which is ultimately inexplicable. Consider a sheet of music, the grooves on a gramophone record, the distribution of magnetic particles on a tape, the sequence of digital codes on a CD, the way the pianist moves her fingers, the vibrations in the loudspeaker cones and the way the conductor's arms wave. All these, if they refer to the same moment of the same music, must express some common form, but we cannot say what it is. What links all these disparate examples of human activity and production is our perception of them as being connected. It is our thought that links them together, but there is no 'formula' for describing the nature of that linkage, any more than there exists a formula for describing how a particular word or phrase can be used. Thus, to seek a causal relationship between a planet and an event it describes is to be substantially misguided about the nature of language.

While we can see that the astrological language can signify qualities that may not be definable in other linguistic systems (as is the case with all languages) there is a tendency to ask of astrology: how does its language work? We can give example of how any language can be used, as can the astrologer, who can also offer alternative descriptors for the non-astrologer, but we cannot step outside of language while simultaneously using it. To ask how a language works is, for Wittgenstein, an example of 'a confusion expressed as a question.' It is a confusion because it is framed in the language of science while addressing something that neither science nor philosophy can answer. We can find out how a machine works by taking it apart and looking at it, but we cannot do this with language for we remain within its structure and effects.

The impossibility of seeing what is 'behind language' is wonderfully illustrated by Derrida[14] with a metaphoric allusion to a mirror. The mirror might reflect the world's reality, and also give us a picture of ourselves, but what makes the image possible resides in something unseen -the mirror' s silver backing. Language always depends on something that remains out of sight, and there is a similar limit on our ability to conjecture what this might be, as we cannot step outside of what it is.

A famous example here would be Frege's and Russell's attempts to define the underlying rules of mathematics. Both made claims to do this, but Wittgenstein noted that whatever they came up with would still be a mathematical expression, and hence fall under the auspice of what they endeavoured to get beyond.[15] While we may have new insights into our world -as did Frege and Russell and many other innovators -using language differently to illuminate new possibilities is still using language, and we cannot go beyond what it gives us, as there would be no way of saying what that was. While none can ignore the implications of these two observations - that we cannot get behind language to explain it or describe circumstances that lie beyond our words - we can at least acknowledge the problems that emerge when our language 'bewitches us' into reifying what are essentially metaphorical interpretations. Hence Wittgenstein's gnomic conclusion to the Tractatus: whereof we cannot speak, thereof we should remain silent warns us against trying to fill the silence with the noise of theories rather than simply observing, though the urge to do so is hard to resist.

All languages have their mysteries and in this astrology is no different, even if the way in which it discloses ourselves and the world may seem particularly mysterious when we first encounter it.

Go to Part One: Language and the Chart

Mike Harding

Mike Harding spent many years as a Faculty Council Member in the Faculty of Astrological Studies, and was Director of the Faculty’s Counselling Within Astrology course. He is also a past chairman of the Astrological Association of Great Britain and of the Association of Professional Astrologers. He worked together with Charles Harvey for many years, primarily in business and mundane astrology and wrote with Charles the invaluable book 'Working with Astrology'. Mike is also author of 'Hymns to the Ancient Gods' and of numerous articles for various astrological publications. Currently, Mike is working as an existential psychotherapist and is Chair of the Society of Existential Analysis. He is interested in the cross-over points between psychoanalysis, existential practice and the ancient wisdom traditions. Mike is also a Course Leader, Foundation Programme, at Regent's University London in Humanities & Social Sciences. (Photo: Regent's University.)

Footnotes for Written in the Stars: The Language of Astrology, Part Two

[11] Irigary, L.(1994) Thinking the Difference, The Athlone Press, London. Page 25

[12] Seymour, P. (197) The Scientific Basic of Astrology, Quantum Books, London

[13] Eysenck, H & Nias, D. (1982) Astrology: Science or Superstition? Maurice Temple. London

[14] Derrida, J (1986) The Tain of the Mirror. Harvard University Press, London

[15] Monk, R (1990) Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Vintage Books London, page 307